Infrastructure will take the stage this weekend as a theme of the second televised debate between Indonesia’s presidential and vice presidential candidates for the 2019 election.

As the incumbent, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo will have plenty to talk about – for each year of his term since 2015, his government claims to have built more than 3,000 kilometres of major roads, almost 30,000 metres of bridges and 44,000 units of low-income housing, as well as toll roads, dams, airports, irrigation systems, rail lines and more.

Of course, his opponent Prabowo Subianto may pick up on the fact that some of this spending has fallen through the gaps – in 2017 alone, as many as 241 cases of corruption and bribery were identified in the infrastructure sector, incurring state losses of up to Rp 1.5 trillion (about AU$151.5 million).

So what are the costs and benefits of the government’s spending spree on infrastructure? Where is the money coming from? And how can we be sure that it’s going to the right places? These were the basic questions framing recent analysis of the national budget conducted by Seknas Fitra, the Indonesian Forum for Budget Transparency.

Spending big on infrastructure

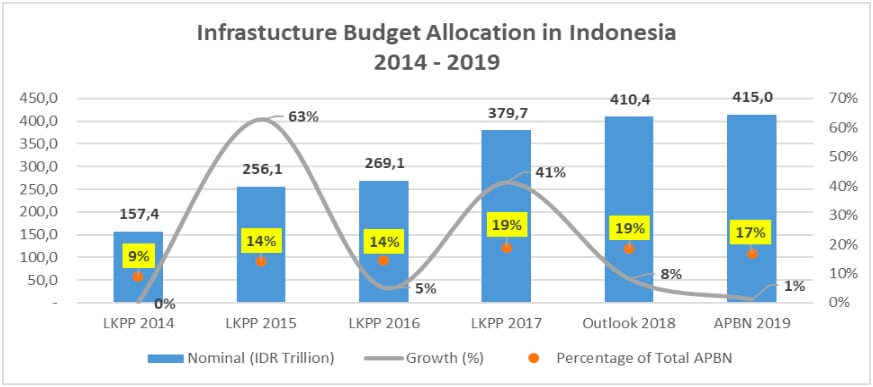

The ascension of Jokowi’s “Working Cabinet” in 2015 was marked by a significant jump in infrastructure spending. The Rp 256.1 trillion earmarked for infrastructure from the national budget that year represented a 63 per cent increase on the amount allocated in the final year of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s “United Indonesia Cabinet”.

Since then, infrastructure spending has continued to increase every year – the biggest increase came in budget year 2016-2017, when the sector’s allocation rose by Rp 110.6 trillion, an increase of 41 per cent. Over the president’s five-year term, infrastructure has accounted for an average 17 per cent of total state spending.

This flow of resources for infrastructure has affected other sectors as well. Given that infrastructure development is considered to play a role in public welfare, the government may be able to claim its success in reducing the poverty rate to a single digit (9.7) was made possible by its increased infrastructure spending. Yet economic growth still hasn’t budged from an average of 5.14 per cent, according to year-on-year numbers from Statistics Indonesia (BPS).

Falling through the cracks

Not all the money being spent on infrastructure has reached its intended target, to say the least. Cracks in state bodies and institutions have been exploited to leak funds into the wrong hands, incurring trillions of rupiah in state losses.

Some Rp 1.5 trillion was lost from the infrastructure budget in 2017, including Rp 34 billion in bribes, more than double the previous year’s losses of Rp 680 billion. Investigations by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) and Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) in 2018 found the biggest leaks in transportation infrastructure projects, at around Rp 575 billion in state losses, followed by funds diverted from infrastructure for education (Rp 43.4 billion) and for villages (Rp 7.9 billion).

Exploitation has often been brazen. At the end of 2018, the KPK identified two officials from PT Waskita Karya, a state-owned enterprise that operates in the field of construction, believed to be connected to the loss of an estimated Rp 186 billion in state funds via 14 fictitious projects that they were supposedly handling. These projects included made-up work on flood canals in Jakarta, revitalisation of rivers and dams in West Java, a hydroelectric project in Papua, and at the Kualanamu airport in North Sumatra.

Further, eight figures from the Ministry of Public Works and Housing have recently been accused of pocketing funds through their work on a drinking water supply system for several regions. Their alleged method? Requesting an unauthorised ”fee” of up to 10 per cent of the value of each project.

Another known leaking point for public money is through funds meant for the regions. Special Allocation Funds are allocated from the state budget with the aim of improving the quality of basic public services in the regions, and reducing inequalities between regions. In 2019, Rp 69.3 trillion has been budgeted for this purpose.

It’s through the process of disbursement that amounts begin to disappear. Submissions for these funds are made to the National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas) and the Finance Ministry, and must have the approval of the House of Representatives (DPR) – meaning that opportunities abound for ways to manipulate the process.

Seven cases of corruption related to these regional funds went on trial in 2018, totalling state losses of at least Rp 66.1 billion. In one high-profile case, House Deputy Speaker Taufik Kurniawan was arrested for alleged bribery in the disbursement of funds for the district of Kebumen in Central Java. In West Java, the district head of Cianjur was accused of requesting a fee for the construction of a junior high school building. Yet more cases involved the district head of Malang, the mayor of Tanjung Pinang, a member of parliament and the head of the Arfak Mountains district in West Papua.

Up for debate

Infrastructure holds enormous potential to accelerate economic growth, absorb a growing workforce, and improve Indonesia’s human resources. It’s therefore vital that those vying to lead the country in this weekend’s debate show commitment in a few key areas.

The first would be the commitment to finalise and maintain existing infrastructure projects. The second would be to strengthen the performance of auditing bodies set up to monitor infrastructure projects, such as the International Government Auditing Unit (APIP) established by the Inspectorate and State Development Audit Agency (BPKP). Third would be to strengthen the role of external monitoring institutions, like the State Audit Agency (BPK) and KPK, to identify and close the cracks allowing corruption to drain infrastructure budgets.

Finally, there is a need to increase the role of citizens in planning, budgeting and implementing infrastructure projects, as well as in taking responsibility for their completion and maintenance. After all, they are the ones for whom all this spending is intended.

The views and opinions expressed in this post do not represent the views of the Australian or Indonesian governments.

*Penulis adalah: Sekretaris Jenderal FITRA periode 2018-sekarang. Saat ini sedang menyelesaikan kuliah Kajian Gender di Pasca Sarjana Universitas Indonesia. Lebih dari 15 tahun aktif di dunia NGOs. Fokus isu yang didalami antara lain terkait dengan ekonomi makro, anggaran publik (APBN/APBD), kesetaraan gender, dan kebijakan publik.